The Novels and Their World

The novels centre around a man called Canio (or Aulus Claudius Caninus, as he christened himself – although christened is hardly the correct word for a man whose default position, in a superstitious age, is to believe in very little). First encountered in The Moon on the Hills, when he was a soldier with the fairly low rank of ducenarius, he is now the owner of a villa estate in the North Cotswolds, an estate which he bought with a fortune in gold acquired by questionable means.

They are mostly set in the province of Britannia Prima (roughly the western half of south/central Britain), into which Christianity seems to have made only limited inroads and where belief in the old, dark gods and goddesses, with its associated undercurrents of mystery and magic, was still strong.

Britain was part of the Roman Empire from 43 to 410AD, part of an Ancient World which had its roots in the lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea. And during those years Britain too possessed something of the exoticism of that Ancient World, something which, once gone, was never to return.

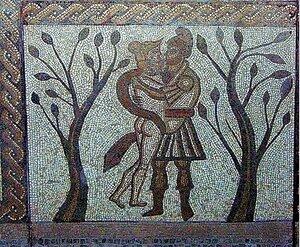

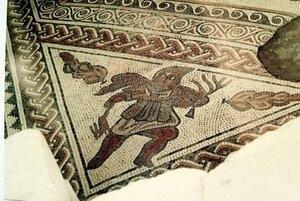

In Britain, the first half of the fourth century was the high summer which saw the building or enlarging of imposing town houses and country villas, the finest of which rivalled anything to be found north of the Alps, both in sheer size and the magnificence of their floor mosaics and wall frescoes.

But all summers die, and by the 360s the world that had produced the rich villa culture of southern Britain was in slow decline, already on the downward spiral that was to end in the formal abandonment of Britannia as a diocese of the Empire in 410. Yet even in decline that world still possessed lingering echoes of a civilisation that was to be almost wholly absent in the muddy centuries which followed.

The causes of that decline were both empire-wide and local. In Britain there had been the invasion scares of 343 and 360 (the latter when the Picts are thought to have crossed Hadrian’s wall) followed by the devastation caused by the Barbarica Conspiratio of 367, those seemingly co-ordinated invasions by the Picts from what is now Scotland, the Scotti and others from Ireland, and (possibly) by Saxons and Franks from across the North Sea. Added to this was the lingering trauma of the reprisals carried out against the wealthy British supporters of the Gallic usurper emperor Magnentius which followed the final crushing of his rebellion in 353.

Yet, despite these troubles, even in the mid-360s Britain had still basked in the glow of a golden age which few then alive realised would never return. But their world was changing, and not for the better.